Summary

Religious persecution is a hotly debated topic in India. But instances where people of a religion are killed by kings or warriors of their own religion are rarely looked into. A dispassionate look at such incidents can be done so by visiting those time periods and understanding the prevailing social, political and economic situations. This will help us understand the complex history of a diverse country like India and answer many questions raised in the on-going debates on religion based conflicts. This article looks into one such phase in the history of Karnataka and modern Hinduism, where people belonging to the Lingayat sect were persecuted and mass murdered by a king who practised Hinduism.

Conflicts of late 17th and 18th centuries

Thanks to religion-based politics being practised by various political parties, we often hear of the many conflicts between kings of different faiths, which resulted in the death and destruction of people belonging to the losing king’s faith. Rulers, particularly those claiming to be Muslim, are often accused of being anti-Hindu and carrying out massacres of non-Muslims. Like other regions of India even the erstwhile Mysore Kingdom and modern day Karnataka saw direct conflicts between rulers of different faiths over religious issues. For instance, the forces of the Muslim Sultanate of Bijapur (who ironically were allied with the Hindu Marathas) had a not-so-pleasant tiff with Hanumappa Nayak a Hindu Nayaka ruler at Basavapatna, which was apparently vitiated by religious factors (1).

It is interesting to note that the persecution of people or religious groups has a long history in this erstwhile kingdom, irrespective of the ruling king’s faith. While historians state that many Sufi Muslims escaped the Muslim Bijapur Kingdom and found refuge in the domains of the Hindu Mysore Wodeyar kings, when Alamgir Aurangzeb, the Moghul Emperor invaded and annexed this part of India (2), there are similar accounts of ordinary residents of modern day North Karnataka, mostly Hindus, suffering from Shivaji’s invasions- including his destruction of towns like Hubli, Karwar, Ankola etc (3). History suggests that the Maratha Empire he left behind continued the pillaging and laying waste to towns, villages, temples and farmlands in the neighbouring kingdoms. Mysore was one of the kingdoms at the receiving end of the Maratha incursions, both when it was being ruled by the Hindu Wodeyar dynasty as well as under the Muslim kings Haider Ali and Tipu Sultan. The later period of these Maratha incursions also saw Sringeri Mutt, among the holiest of Hindu shrines, being laid waste and its Brahman priests massacred by them (4) (5). Documents suggest that Tipu Sultan, a Muslim king who has serious allegations of being anti-Hindu, helped the restoration of the shrine (6). According to Kirmani, a contemporary and biographer of Haider Ali as well as Tipu Sultan, indeed the earliest incursions of the destructive campaigns of Mysore rulers into the Malabar coast happened under the Hindu Mysore Wodeyar rulers in 1750s. In fact, Nawab Haider Ali’s first foray into this region happened when he was sent by the Mysore Maharaja on a campaign to reduce the Malabar coast, in which both the Hindu Nairs and the Muslim Mappillas are said to have opposed him and suffered as a result (7). But these events overshadow the violent conflicts between rulers and people of the same religious faiths, thanks to politics.

Hidden massacres of Lingayats in 17th century

Tipu Sultan had conflicts with the Hindu Nairs of Kerala as well as the Kodavas (8). His forcible religious conversions are a major point of debate more so ever in recent times, with passionate claims and counter claims. However, less known is the fact that religious persecution and massacres of the peaceful Hindu Lingayat sect were alleged to have been carried out by the Hindu Mysore Wodeyar king Chikkadevaraja Wodeyar towards the end of 17th century(9).

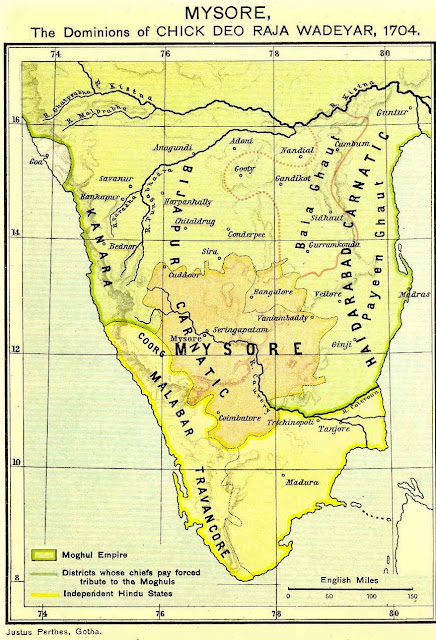

|

'The dominions of Chikkadevaraja Wodeyar on his death in 1704.'

By Charles Joppen - of Professor Frances W. Pritchett, Department of South Asian Studies, Columbia University, PD-US, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=20915519 |

Edgar Thurston a well-read British Raj anthropologist authored many books on the caste and caste system of south India including 'Castes and Tribes of South India' which he co-authored with Rangachari. In the book the authors also delve into the migration of communities to the neighbouring states. In Vol. 3, published in 1909, they give an interesting account of Kannadigas (Kannada speaking people, whom they refer to as ‘Kannadiyans’) who were found in the British administered Madras Presidency (modern state of Tamil Nadu). These Kannadigas were found to be Lingayats.

|

| Source: Castes and Tribes of South India, 1909 |

On the question of the date and reason for their migration this is what the authors write:

“The earliest date which can, with any show of reason, be ascribed there to seems to be towards the end of the seventeenth century, when Chikka Deva Raja ruled over Mysore. He adopted violent repressive measures against the Lingayats for quelling a widespread insurrection, which they had fomented against him throughout the State. His measures of financial reform deprived the Lingayat priesthood of its local leadership and much of its pecuniary profit.”

This frustrated the Lingayat farmers and traders alike. In supporting their argument, the authors quote Wilks, a well-known British historian of Mysore Province. Wilks in ‘Historical Sketches of the South of India’ (1817) states the following (10)

"Everywhere the inverted plough, suspended from the tree at the gate of the village, whose shade forms a place of assembly for its inhabitants, announced a state of insurrection. Having determined not to till the land, the husbandmen deserted their villages, and assembled in some places like fugitives seeking a distant settlement; in others as rebels breathing revenge.”

|

| Image for representation only |

In response, Wilks suggests that the punishment was swift with the Mysore king using treachery as one of the tools to assassinate over 400 Lingayat priests.

“ChikkaDeva Raja, however, was too prompt in his measures to admit of any very formidable combination. Before why they migrated they concluded that proceeding to measures of open violence, he adopted a plan of perfidy and horror, yielding to nothing which we find recorded in the annals of the most sanguinary people. An invitation was sent to all the Jangam priests to meet the Raja at the great temple of Nunjengod, ostensibly to converse with him on the subject of the refractory conduct of their followers. Treachery was apprehended, and the number which assembled was estimated at about four hundred only. A large pit had been previously prepared in a walled enclosure, connected by a series of squares composed of tent walls with the canopy of audience, at which they were received one at a time, and, after making their obeisance, were desired to retire to a place where, according to custom, they expected to find refreshments prepared at the expense of the Raja. Expert executioners were in waiting in the square, and every individual in succession was so skilfully beheaded and tumbled into the pit as to give no alarm to those who followed, and the business of the public audience went on without interruption or suspicion.”

Wilks further writes that the Maharaja did not stop at the killing of the above 400 priests at Nanjangud but issued orders for the destruction of all Jangam Lingayat Mutts and their followers. This, he suggests, led to the destruction of over 700 mutts and numerous deaths of Lingayats.

"Circular orders had been sent for the destruction on the same day of all the Jangam Mutts (places of residence and worship) in his dominions, and the number reported to have been destroyed was upwards of seven hundred ....

This notable achievement was followed by the operations of the troops, chiefly cavalry. The orders were distinct and simple- to charge without parley into the midst of the mob; to cut down every man wearing an orange-coloured robe (the peculiar garb of the Jangam priests)."

A rationale discourse for a mature democracy

The nation is currently witnessing an unprecedented wave of politics based on conflicting versions of history. In the loud din of ‘for’ and ‘against’, we are overlooking the social context under which historical events and conflicts occurred. If conflicts between kingdoms, in what today is India, originated exclusively from differences in religions of the opposing kings why do we have the numerous instances of rulers professing one faith killing people of the same faith? This question may help our political discourse on history become more rationale. That will not only help reduce friction between various social groups but also help the country to be seen as mature democracy in the world eyes.

---

References:

(2) Personal communication with Muneer Ahmed Tumkuri, Tumakuru-based Historian and Author, 04 Nov. 2016

Wilks’ work is quoted by many British writers and also Mysore historians of 19th and 20th centuries including the below works

---

You may also like to read

Comments

Post a Comment